How are data created?

Related project

4M CaucasusThe important (and sometimes fatal) first question that needs to be asked.

Context:

netgazeti.ge is a news website based in Tbilisi, Georgia. Thanks to CFI, I have been working with them for almost two years now on their business model, the switchover of their CMS and two 'new' formats of journalism: long-form journalism and data journalism.

The following is an account of a data-journalism project that is still at the drawing-board stage… for the time being, anyway.

The first step of data journalism is gathering data, but this involves more than simply obtaining figures – you need to be able to critically assess them in order to ensure that they are used correctly.

Georgia – the promised land of data journalism

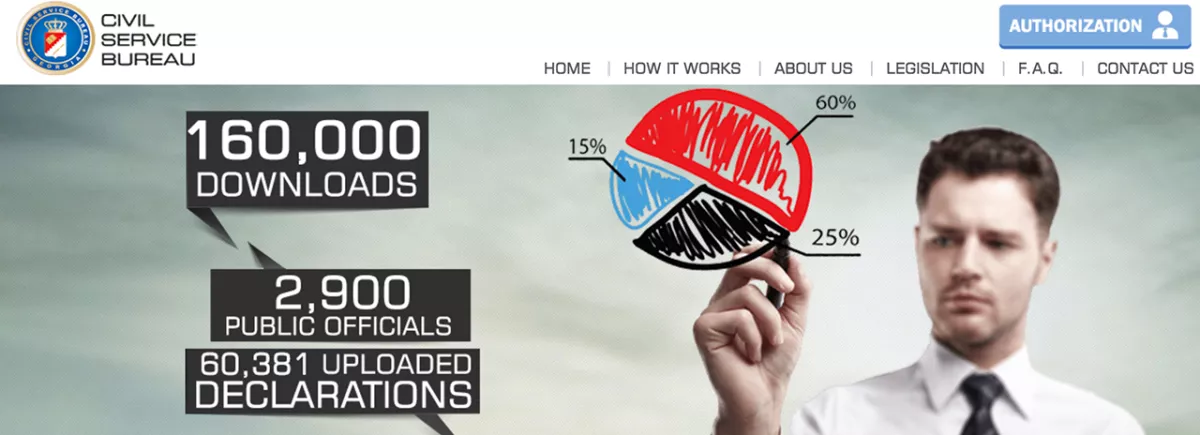

Georgia is a country with an abundance of resources, which include, among other things, a great many datasets. Some of them have been compiled directly by the government, such as declaration.gov.ge, while others originate from foreign associations and foundations which believe that one of the ways to further speed up the country's transition to ever greater transparency is to publish data online – see the Caucasus Barometer, for example.

For five years now, elected officials have been required to publicly declare their assets.

Yes, my France-based colleagues, you read that right. Can you imagine the reaction in France if the same thing applied there? "You're a French politician and you've publically declared your assets?!? You cannot be serious!"

Initially, the documents were scanned forms that were filled in by hand, and so in some cases were difficult to read.

However, these were replaced two years ago by PDF forms that are completed electronically, which is far more practical.

With the help of

Ettore Rizza, an independent journalist who specialises (in particular) in data extraction, a list of over 5,400 declarations for 2015 has been compiled.

The editorial team at netgazeti, just like their counterparts at other media outlets, regularly use this database to get information on Georgia's politicians, such as the number of cars they own, their property portfolios, and even how much cash they have in their accounts.

Faced with such a wealth of (relatively) well-ordered information, as aspiring data journalists it is only natural for us to wonder if a more user-friendly database could be set up, giving readers the opportunity to ask questions like, for example, "Which politicians have more than 50,000 dollars in cash?", "How many apartments do judges own on average?" or even "In which cities are their properties located?".

To do that, we first need to analyse the PDF files. This allows us to:

. identify the structure of the PDF files,

. and thus envisage the structure of the database,

. and, by comparing several sample PDF files, attempt to understand how they are filled in by the politicians.

And it's here that we've come across one of the biggest problems concerning data: the fact that it is not uniform, which makes it impossible to derive a standard blueprint from it.

The non-uniformity of the data

In order for a database to allow different entities (politicians in this case) to be compared, the information relating to those entities needs to have the same characteristics.

What have we noticed from focusing on these PDF files?

There is nothing to indicate the period to which they relate. Does a PDF file placed online in December 2015 contain information about 2015, or does it instead relate to the previous year (i.e. 2014), which is the only closed year? Like tax statements or company balance sheets, is the year in question actually the previous year?

We've read the law: it only refers to the obligation to make an annual declaration, but gives no details on the rules for compiling it.

And this despite there being an abundance of information published on the website – the first sentence of which quite frankly does not appear to reflect reality.

Second type of data non-uniformity: information on bank accounts. Politicians must give the details of all their bank accounts: the name of the bank, the balance, the currency, loans, debits, etc.

The problem is that some declarations are not clear about the nature of those accounts; there is in particular a fine line between the notions of current accounts, loan accounts and savings accounts.

We posed these questions to a bank and a specialist law firm. The answers we received are still very evasive.

We contacted the team that manages the website on which the declarations are published: nobody knew the differences between those three types of accounts.

We approached one of the politicians who completed this document: she was unable to provide us with any explanations since she was not affected by those various accounts, and politicians had not received any instructions as to what they needed to report. This is still a declaration, let's not forget.

It is difficult to establish the right structure for the database

As well as the non-uniformity of data, there is also another long-standing problem: the impossibility of establishing a suitable structure for the database. Without a structure, there is no database. This does not involve creating columns here, there and everywhere and then filling them with data that nobody understands: this could lead to a plethora of errors in future readings.

The structure is essential: through it, we are able to editorialise the data. A data-journalism project must fulfil certain objectives, such as highlighting an issue, giving arguments for future interviews, or making it possible to find stories. This is all only made possible if the database can be consulted in such a way as to address those questions.

Lastly, there is one more cause for concern: with three different currencies, how can assets be compared with each other? We have come up with our own (debatable) solution: the average exchange rate for the year to which the data relate should serve as a basis. This is why it is important to know the period to which a declaration relates.

And so, for the time being at least, we find ourselves standing before a potential goldmine of data, but we haven't yet identified a satisfactory process for exploiting it smoothly. If you've got any ideas that could help us put such a process in place, then please don't hesitate to tell us!